Jesus puts a Question to Pilate

Day I.

In the Gospel of John, one of the last things to happen to Jesus does before his death is a question and answer session with Pontius Pilate (see John 18: 1 – 19:30). Pontius Pilate is a well-known name to readers of the New Testament, but as an historical figure little is known about him. What is known is very telling, however. He was the Roman Procurator in Judea from about the year 26 to 36. The Procurator’s job combined several offices: governor, judge, tax collector, and commander of a band of soldiers that functioned a bit like a police force. Quite a bit of power was concentrated in the Procurator. Yet, for this reason, the Procurator’s job was an awkward one.

In the Gospel of John, one of the last things to happen to Jesus does before his death is a question and answer session with Pontius Pilate (see John 18: 1 – 19:30). Pontius Pilate is a well-known name to readers of the New Testament, but as an historical figure little is known about him. What is known is very telling, however. He was the Roman Procurator in Judea from about the year 26 to 36. The Procurator’s job combined several offices: governor, judge, tax collector, and commander of a band of soldiers that functioned a bit like a police force. Quite a bit of power was concentrated in the Procurator. Yet, for this reason, the Procurator’s job was an awkward one.

Pilate was caught in the middle. He needed to garner support from the Jews in order to please his own authority figures – but too much lenience towards the Jews was sure to wrong-foot him with Rome. He needed to be seen to stand for the official line in order to further his own career – a factor that made it more difficult to please the Jewish population under him. There is historical evidence that he clashed with both sides and pleased no one. Finally, in the year 36, he was deposed as Procurator of Judea and recalled to Rome. It is tempting to feel a bit sorry for Pilate in the situation that developed with Jesus and the Jews, and to see him as the harassed middle-man caught in a slightly bizarre and violent drama that he neither caused nor fully understood. There is certainly an element of that in the story. And perhaps Jesus, too, gave him the benefit of that doubt. Let’s examine the narrative and try to see what really drove Pilate, and whether he deserves our compassion.

In the passage immediately preceding the dialogue between Pilate and Jesus (John 18: 1-11) we learn that Jesus had been arrested the evening before by a cohort from the Roman garrison, and a group of guards sent by the chief priests and Pharisees, all with weapons and torches. This is all highly manipulative and directed to the intimidation of Jesus, but Jesus has never been cowed by intimidation techniques before and does not start now. He takes the initiative, steps forward, addresses this mob of soldiers and angry, self-righteous priests. He poses the first of many questions he will ask in the final events before his crucifixion. He says directly, ‘Who are you looking for?’

This question immediately exposes his opponents’ falsity. It says in effect that all this melodrama is simply not needed. “State your business for all to hear,” Jesus seems to say. “I know what you are about already and I will come with you without force.” Indeed, when had Jesus ever responded to violence with violence? He has the upper hand here, reading the situation clearly and responding to it from the perspective of his own spiritual depth and emotional courage.

When the mob spokesman admits that they are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, he simply owns his identity in the words, ‘I am.’ These two words are explosive ones. Jesus’ Jewish opponents feel it intensely and are shocked. Many reel backwards and fall down. Jesus has identified himself using the words for the holy name of Yahweh, the I AM word, first revealed to Moses at the burning bush, and so sacred that it is never uttered by devout Jews. But Jesus cannot disown his very being, and he knows that the time has come for him to be absolutely clear and unequivocal about who he is.

I have written this reflection as part of my own lectio divina, and I hope it may help others as they meditate on this passage of scripture. I recommend that only one section of this reflection be read each day, so that the seed of the Word has a chance to settle in the good soil of the heart before we move on to the next reflection. Let’s stop for today and resume tomorrow.

Day 2.

We left Jesus in Gethsemane surrounded by a lynch-mob. Jesus, as always, is master of himself and his situation. He handles his enemies with both courtesy and courage, and has just identified himself to them with the words ‘I AM’, the holy name of Yahweh, so sacred it is never even uttered by devout Jews. There is a moment of shock, and then a certain amount of chaos follows. Peter, probably crazed with panic, resorts to violence and cuts off the ear of the high priest’s servant. Jesus reprimands him (and in other gospels, heals the servant), expressing his knowledge that he is destined to suffer a conflict of epic proportions, and that it has already begun. He will undergo it on his own terms, though, and not according to the impulses of mob violence. Once the principal characters in the mob regain control of their wits, however, they seize Jesus, despite his evident willingness to cooperate. They are determined to treat him like a dangerous criminal. They bind him and no doubt shove and frog-march him to the palace of Annas, the high priest.

Accordingly, the high priest questions Jesus about his teaching, and although the Gospel of John does not record the exact questions here, it does record Jesus’ answer. Jesus affirms the futility of asking any questions about his teaching by saying that he has been teaching openly for all to hear for a long time, and has never made a secret of any of his doctrines. Then he asks his questioner a simple question of his own: ‘Why ask me? Ask my hearers what I taught.’ Jesus is afraid of no man, and responds to the high priest as to an equal. He knows that the best advertisement for his teaching is found not in his own summary of it but in what has actually been learned by those whom he taught. Jesus earned a slap in the face and a rebuke from one of the guards for this perceived impertinence to the high priest: ‘Is that the way you answer the high priest?’ Undeterred, Jesus answers the guard’s question with a question: ‘If there is some offence in what I said, point it out; but if not, why do you strike me?’ Apparently, this question hangs there, forever unanswered. Meanwhile, Annas, possibly realising that he is out of his depth with Jesus, and cannot possibly win in a verbal exchange with him, sends Jesus on to the next questioner.

Day 3

We are about to look at the dialogue between Jesus and Pontius Pilate in the Gospel of John (Jn. 18:1- 19:30). Jesus, after being questioned by the chief priests Annas and Caiphas, is now marched, still bound, from Caiaphas’ house to the Praetorium. The Praetorium is the palace of the Procurator, Pontius Pilate, and here Jesus will undergo Pilate’s interrogation. We have already noted that Pilate, as governor of Judea, acted as a supreme judge in his district. Therefore he alone had the authority to impose the death sentence, which is what the Jewish leaders who handed Jesus over want Pilate to do. Jesus’ arrest and trial so far have gone on all night and it is now morning. Jesus is by now more than exhausted, surely.

Jews were not allowed to go into the inner court of the Praetorium on pain of incurring ritual impurity for entering the dwelling of a gentile, so Pilate must meet Jesus’ captors outside – a concession which must have rankled with Pilate, I imagine. Nonetheless, he complies, and questions them about the reasons behind Jesus’ arrest. According to the text, they claim simply that Jesus is a criminal and deserves death, and that they are not allowed by their religion to pass the death sentence. They do not specify what Jesus has done to deserve it (see Jn. 18:28-32). Pilate, none the wiser for this exchange, must now question Jesus about the reasons for his arrest.

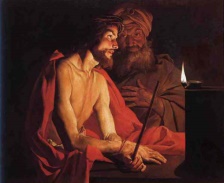

Pilate returns to the inner court of the Praetorium, summons Jesus and begins a highly revealing exchange with him. This is the part we’ve been waiting for in this reflection. We are trying to ascertain what kind of man Pilate is. Should we feel sorry for him?

In Jesus and Pilate we see two men meeting face to face who could not possibly have been more different. Pilate is doubtless a busy man, and with an abruptness suggesting that his temper has been significantly shortened by the preliminary exchange with Jesus’ captors and their vague answers to his questions, asks Jesus the only question that could have any real interest to him, or any bearing on his judgement of Jesus: ‘Are you the king of the Jews?’ Immediately, we see that the issue for Pilate is power. How much power does Jesus really have, he wants to know?

Pilate must surely hope that Jesus’ power is a trumped up affair, threatening to no one. He had probably encountered mad prophets before – they were not unusual in the Judea of Pilate’s day. So, Pilate’s question would, Pilate hopes, set such a prophet up to expose himself as a rant and rave religious fanatic. A wild-eyed diatribe on Jesus’ part would be most useful to Pilate and enable him quickly to dismiss Jesus as long-winded but essentially harmless; then Pilate would be free to move on to the more important business of the day. It is easy to imagine the slightly mocking tone of voice in which Pilate asked his question, much as one might use to a rather ill-behaved child, perhaps, or to someone whom one has already mentally pigeon-holed as not worth taking seriously.

In our reflection, we have entered upon an extremely charged scene, emotionally. The air is fairly crackling with it. The Son of God is undergoing a trial of sorts by someone who is absolutely clueless with regard to his identity. Let us simply be with this highly uncomfortable scene for a day, live with it, and with its questions.

Day 4.

We are looking at Jesus and Pilate in the dialogue occurring towards the end of the Gospel of John in order to discover what light might be shed on the person of the enigmatic Pilate – and through this understanding of Pilate we hope to gain a new awareness of Jesus. The dialogue has barely begun, but Pilate has already exposed something unlovely: his impatience with the entire affair – a fact which in itself was insulting to Jesus, and must have registered as such with Jesus. Pilate asks Jesus bluntly, ‘Are you the king of the Jews?’

Jesus is calm, masterful – despite the trauma of his arrest and of being up all night and being questioned already by the high priests, slapped by guards, bound and pushed about – despite the fact that he knew that his hour had come. Or, rather, because of it. Jesus’ response to Pilate’s question is consummately intelligent and not in the least expressive of the mental derangement which Pilate probably hoped to find in him and which might have made his task so much easier. Jesus, in answer to Pilate, asks a question of his own: ‘Do you ask this of your own accord, or have others said it to you about me?’

Astonishing question under these circumstances. What can Jesus mean by it? Jesus knows his hour had come. Whatever Pilate’s answer, it could not possibly have altered Jesus’ destiny. Jesus was the Lamb of God and his hour had come. Moreover, Jesus’ question cannot have been an attempt to gain time in order to plot his escape. It can only have come from his awareness of Pilate as a human being in need of salvation. Here is a condemned man, offering salvation to the one who would condemn him. How?

Although Jesus has already been insulted by Pilate, it is never his way to return insult for insult. As always, Jesus is reaching for the deepest level of the person to whom he is speaking. He sees that Pilate is not master of his destiny, is not his own man, but he could be if only he would look inward and ask himself the vital question, “Do I really want to know if Jesus is king of the Jews for my own sake?” Jesus wants Pilate to question Pilate. This is the only way anyone gains true self-hood – through self-questioning as to the meaning of existence and the meaning of one’s choices.

Jesus’ thirst for souls is never quenched, never shelved, forgotten, or given up. To his last breath he is offering salvation to all. Jesus sees clearly that Pilate, on one level, is a man to be pitied. He is a puppet of higher political powers. History suggests that probably most of Judea regarded Pilate as an inept governor, always acting with one eye turned towards those who might be watching him, and rarely, if ever, acting, or even thinking, without being jerked into position by those puppet strings. Jesus, however, seems to pay Pilate the compliment of taking him seriously as an independent thinker, able to lay claim to his own actions and act from within his own centre of freedom.

But, Pilate? Jesus knew that Pilate would not be capable of questioning himself immediately. He was habituated to ignoring his conscience and silencing his inner questions. But later. Later, Jesus’ question might return to Pilate. And then, Pilate might have a chance to become a man. Now, however, Pilate knows that others are pulling his strings, and although he hates it, he thinks that getting more power for himself will solve his problems. He will allow himself to be a puppet to any degree if this seems to be the most effective way of eventually obtaining more power. Power is what everything is about for Pilate; it is the mental lens through which he views everything he does. Naturally, his conversation with Jesus is coloured by these preoccupations.

But, as far as Jesus is concerned, the preoccupations are entirely other. The conversation with Pilate, in Jesus’ view, is not about political power but about truth and freedom.

Day 5.

Do you ask this of your own accord or have others told you about me? This is the first question Jesus puts to Pilate, in answer to Pilate’s question, ‘Are you the king of the Jews?’ In the dialogue between Pilate and Jesus, as we said yesterday, the two men are motivated by completely opposing psychological preoccupations. For Jesus, the dialogue is about truth and freedom. And, do not forget, the dialogue is – astonishingly – about Pilate’s salvation. For Pilate, on the other hand, power is the only thing he cares about. Truth and freedom barely enter into his thought process at all, it seems. At this stage, if Pilate had been an entirely different kind of man, he might have used Jesus’ question as a springboard to ask himself: “Do I ask this of my own accord? Do I want to understand this man and his message? Does his message speak to me on the level of my spirit, my heart?” Jesus pays him the compliment of suggesting that such questions might be important to Pilate. But Pilate does not move out of his habitual mind-set.

Pilate exposes his superficiality by retorting first, ‘Am I a Jew?’ Here, Pilate reveals, tragically, and with the tone of incredulity that his words suggest, that he thinks it should be obvious to Jesus that he has no spiritual leanings whatsoever towards Judaism and its tenets. He goes on to make this completely clear, saying, ‘It is your own people and the chief priests who have handed you over to me.’

Pilate has no vested interest in Judaism as a belief-system. But he is a man who likes at least to grasp the facts of a case, and here Pilate is flummoxed. Jesus has been handed over by members of his own religious group. Like a sniffer dog looking for drugs, Pilate gets a whiff of a level of power in Jesus that he cannot quite identify. Clearly, Jesus has some sort of power or he would not be so threatening to the chief priests of his religion. He asks Jesus to explain: ‘What have you done?’ What is so powerful about Jesus that his own people are baying for his execution on the obviously trumped up grounds that he is Pilate’s political enemy?

Here follows Jesus’ explanation. Jesus cuts to the only thing Pilate could possibly care about and talks about his ‘kingdom’. He says: ‘Mine is not a kingdom of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my men would have fought to prevent my being surrendered to the Jews. As it is, my kingdom does not belong here.’ Jesus uses the word ‘kingdom’ three times in this brief passage. I imagine Jesus pronounced the word with that emphasis one gives to an expression that is being used in a way contrary to its usual meaning in order highlight that a different point is being made. This subtlety was lost on Pilate. ‘My kingdom’ is a phrase Pilate understands in one way only. Worldly power, riches, domination, influence, kudos. That’s all it means for Pilate. He takes note, and now questions Jesus again, and surely with a sharp edge of sarcasm, ‘So then! You are a king?’ [emphasis mine].

Pilate is not listening. Jesus is trying to say the exact opposite, that he is not a king in Pilate’s sense of the word, that the word ‘kingdom,’ in Pilate’s sense of the word, does not apply to him at all, for he has no soldiers, no public support after the manner of ‘normal’ kings. He is trying to say to Pilate that his ‘kingdom’, if the word must be used, does not operate according to the standards of this world, and it holds absolutely no threat to Pilate and his kingdom. Jesus wants Pilate to know that he wants nothing that Pilate has. But, Jesus is not afraid to imply that he is Lord of a realm, of a certain kind of ‘kingdom’. It just happens to exist on a deeper level than the stage of worldly power, success and domination. But Pilate is way out of his depth. Jesus is too subtle for him, too deep and spiritual – and too dazzlingly brilliant. Pilate is beginning to realise this.

Pilate has no wish to appear ridiculous and precipitate to the public in his handling of this awkward situation. But he wants an easy answer to the problem of Jesus and the Jews. It is still not completely clear to him what the real issues are. His position will not be bolstered by passing an unjust sentence – he knows this much. So, the question of Jesus’ identity needs to be answered. Is Jesus really the usurper that the Jews are making him out to be?

It would be easy to idealise Pilate here for this seeming reluctance to sentence Jesus, but let’s consider the facts as the text gives them. Does Pilate care about Jesus for religious reasons? No. He has already made that abundantly clear. Does he care about Jesus at all? Doubtful. He cares only for the political effect this difficult situation will have on his career. This will become more obvious as the dialogue continues.

Day 6.

If Pilate pleases the crowd he may gain their support, and that would be useful in the future, possibly. So then! You are a king? This is the question Pilate puts to Jesus, and in answer, Jesus repositions the question squarely in Pilate’s domain, where it originated. ‘It is you who say that I am a king,’ he says. Or, the words of Jesus could be fairly rephrased as “It is you who are so determined to make me a king.” Jesus’ statement exposes Pilate’s power-obsession, and makes it obvious that it is he who, out of his own insecurity, insists on seeing this as a power-struggle.

Pilate can’t quite believe Jesus when he implies that worldly kingship and power are not what define him, and are not even what he wants. Again, the sniffer dog is alert in Pilate. If that is true, there must be some other power that Jesus has that has caused this furore. What would that be? Jesus answers this implied question. He now solemnly gives the reason for his very existence, and explains the nature of his power and kingship: ‘I was born for this,’ Jesus says. ‘I came into the world for this, to bear witness to the truth, and all who are on the side of truth listen to my voice.’

Truth is indeed powerful. It has frightened the chief priests enough to turn them into murderers. But they cannot be said to be “on the side of truth.” Quite the opposite. Instead, Pilate, incredulous that such a fuss is being made over a man who is nothing more, in his estimation, than a harassed philosopher, bursts out, ‘Truth?? What is that?’ Or, he might just as well have said, What use is that? Who really cares about truth? Almost no one! Certainly not when truth seems to be challenging the structure of a religion that has been good enough for a very long time. But at least Pilate realises now that Jesus will never be a rival to any political power on those grounds. Pilate thinks that he has at last sussed it. Jesus, in his eyes, is an idealist, and rather absurd. But he does not deserve the death sentence. In Pilate’s judgment, the Jews are also absurd for expecting Pilate to weigh in on their side against Jesus.

Again, we see that Pilate is not “on the side of truth”. He no more recognizes who Jesus is than those who were angling for him to be executed. For Pilate, at least at this stage in the proceedings, Jesus is a fool. And surely, Pilate is exasperated now, as he goes out to the dais and makes his pronouncement to the crowd, ‘I find no case against him.’ A pithy statement implying not that Pilate had any real understanding of Jesus or interest in his mission, but only that Pilate considered Jesus to be no threat to him or to any government. The accusations against Jesus seem unfounded to Pilate, and the mob-violence bizarre. Few authorities in charge of keeping order in their district would feel indifferent about such a situation. But, Pilate is the worst kind of political animal, and not a moralist.

Pilate probably wonders: does all this hate come from only a small but vocal minority? A few pushy crackpots? What about the rest of the people? So Pilate offers the saner majority (if such majority exists) a chance to swing this situation. Pilate says to the crowd, ‘According to a custom of yours, I should release one prisoner at the Passover; shall I release this king of the Jews?’ At last, Pilate seems able to use the K-word without discomfort. He sees that Jesus is a nobody: not rich, not influential, not ambitious; Jesus knows none of the right people. His only claim is that he knows truth and who cares about that? In Pilate’s mind, Jesus is rather a freak, but no more than that. The sniffer dog in Pilate has temporarily gone to lie down. But he will soon be alert again.

Day 7

Pilate is trying to finish with this troubling case. But he cannot shake it; it goes on and on, and soon his scalp is tingling with distress and his blood is running cold. He feels caught up again in something more strange, even preternatural. He is a superstitious man and he is beginning to feel odd (see Jn 19:8). At the suggestion of releasing Jesus, the crowd erupts into violent, near-riot behaviour. They begin to scream for Jesus’ death. It becomes clear to Pilate that there is no ‘sane majority’, and no one wants Jesus to be released. They want Barabbas, the thief and murderer, to be set free, not Jesus. Yet it is also clear to Pilate that Jesus is nothing more than a preacher, with no political aspirations at all. What is going on? What gods are frowning here, skewing this situation further?

Pilate tries to satisfy the crowd’s blood-lust by having Jesus taken to be scourged. Afterwards, the soldiers torture him psychologically and physically by mockery, and by making thorn branches into a crown and forcing it down on his head; they put a purple robe on him and make exaggerated bows before him, saying ‘Hail King of the Jews,’ He is slapped in the face. But it is still not enough for the crazed crowd. Pilate, the opportunist, does not particularly like Jesus; Jesus has nothing that Pilate needs or wants. But even less does he like the way things are going. He knows that whatever happens, the situation has become big enough to be talked about and remembered afterwards. He is anxious about how this will affect his reputation. Pilate tries again. He says to the crowd, ‘Look, I am going to bring him out to you to let you see that I find no case against him.’ And Jesus is brought out in his now physically weakened and bloodied condition, dressed in the purple robe and wearing the thorn-crown. He says nothing. Pilate says, ‘Here is the man.’ Instead of being moved by Jesus’ brokenness and his manifest harmlessness, the crowd’s thirst for Jesus’ death intensifies, and their shouts for his execution increase in volume and violence.

Now Pilate’s pulse begins to race. The situation feels uncanny. His mind spins. His fears increase, as the text says (see John 19:8). He calls Jesus to him again in private and questions him more intensely. Pilate’s questions suggest that he is beginning to feel an eerie sense of the numinous, and that he detects the existence of a conflict on a level he is not accustomed to dealing with. He has rarely, if ever, taken seriously matters pertaining to the spirit world and is completely lost now. He frames a question that seems to me to be drenched in supernatural dread, even though he has no use for religion: ‘Where do you come from?’

Day 8

Is Pilate at last ready to listen? Perhaps. But now Jesus has nothing more to say to Pilate on the subject of his identity and origin. And, after the torture he has just endured, he has little ability to speak with someone whom he now knows does not have the capacity to understand him. So Jesus says nothing at all in answer to Pilate’s question. Pilate is not accustomed to such treatment and chooses this moment to remind Jesus of his power over him – once again, the power fixation – ‘Are you refusing to speak to me? Surely you know that I have power to release you and I have power to crucify you.’

Jesus, even in the extreme weakness of his physical condition, cannot allow these ill-conceived words to stand unchallenged. He somehow manages to dredge up the ability to say now, ‘You would have no power over me at all if it had not been given to you from above; that is why the one who handed me over to you has the greater guilt’ (Jn. 19: 11). Another highly enigmatic statement which would have seemed incomprehensible to Pilate – and possibly to us, too. Can Jesus possibly mean that Pilate’s power over Jesus is positively willed by God the Father?

Jesus’ statements are always multi-layered. Each time we reread scripture prayerfully, we can find new depths in Jesus’ words. This statement is one of his most profound utterances. Let us pause for a moment to consider the implications of Jesus’ words. The Father, whose very existence is goodness and love, cannot will evil, and Jesus’ execution and all the events leading up to it, including Pilate’s knowing or unknowing complicity with the forces of darkness, is incontrovertibly evil. Nonetheless, the Father positively wills human freedom. The political power wielded by Pilate is part of the complex working out of human free will on a world scale – free will, that freedom which results not only in the existence of all that is good and true in the world, but which also allows for the formation of the complex and convoluted structures of human sin – of hatred, jealousy, falsehood, murder, death. Jesus knew from the dawn of his consciousness that his mission was to confront, single-handed, sin and death at its source in a titanic battle against Satan. This was his mission; he understood its demands profoundly, and accepted it absolutely. He never shirked it; he always walked resolutely towards it, foreseeing and predicting clearly that the consequences of his teachings and of his very presence in the world would lead precisely to this moment he was now undergoing. He freely chose this mission, and knew that in fact it was one with his very identity. He gave himself completely to it, holding back nothing, out of his unfathomable love for his Father and for the whole human race. This is why Jesus could say that Pilate’s power had been ‘given from above.’

Once again, Jesus pays Pilate the profound compliment of interpreting him in the best possible light, in saying that the one who handed Jesus over ‘has the greater guilt,’ for Pilate is the quintessential pawn, not merely of the Roman government and the hysteria of the Jewish authorities baying for his execution, but of the entire history of human evil, culminating in the pathetic, confused, self-absorbed political manoeuvres he was trying to make with regard to Jesus. Jesus sees that Pilate is not fully to blame for his actions. His spiritual blindness and his preoccupation with power are moral failings that he has inherited from the human condition time out of mind. But, Jesus also wants to make it clear to Pilate that Pilate’s so called power is the power of a minnow as compared to a whale. It is no power. Pilate’s threats are part of the pattern of primordial evil that Jesus has been confronting all his life, and in his divine nature he would ultimately unseat it, overthrow it.

At that moment, was Jesus buoyed up by this awareness? Speculation here is theologically difficult. We are certainly in the realm of paradox now. We know that Jesus’ sufferings were real and beyond our fathoming. But he had inner resources that we cannot fully comprehend which enabled him to speak as he did to Pontius Pilate, and affirm the deepest truth present in the excruciating events he was undergoing.

The other gospels indicate that Pilate is thoroughly shaken now and wants to put as much space between himself and this intense and enigmatic preacher as he can. In Matthew’s account Pilate, at this point, publicly washes his hands of Jesus and of the whole situation that had descended upon him that morning. But in the gospel of John, Pilate continues to interact with the crowd, bringing Jesus out again before them, broken and bleeding, displaying him to the people, seating him on the important chair of judgment at the Pavement. He probably hoped that the sheer incongruity between Jesus, reeling now from faintness, and the robust figure usually cut by a powerful usurper, might register with the crowd. ‘Here is your king,’ Pilate declares. There are tones of incredulity, even pleading, interlaced with the mocking cynicism of Pilate’s tone, I imagine. But Pilate’s action elicits only an intensification of mob-hysteria, as they scream for Jesus’ execution. And again, Pilate challenges them: ‘Shall I crucify your king?’ And their response, blatant with the kind of hypocrisy Jesus had challenged in them repeatedly throughout his ministry: ‘We have no king but Caesar!’

And Pilate gives up. There is nothing for a politician to do but appease this group, give them what they seem to want and hope they will go away and give him less trouble in the future. And Pilate is first and last a politician. He orders Jesus to be taken away and crucified.

Day 9.

Pilate’s final act in Jesus’ regard is as enigmatic and confusing as anything that has ever occurred in the gospels – or indeed, the history of the world. He affixes a notice to Jesus’ cross reading ‘Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews.’ Why? Why can’t Pilate leave it alone now? Why doesn’t he retreat back into his palace after his sentencing of Jesus, away from all the turmoil? Why does Pilate observe Jesus’ final journey to Golgotha, carrying his cross and turn up himself at Golgotha? The notice was nailed to the cross just before it was raised, or possibly afterwards – the text isn’t clear. Why was Pilate still there? Did he feel that he had unfinished business? Was he ambivalent about the sentence he had passed? Or did he simply want to have the last word, now that Jesus was nearly dead, and probably unable to say anything more?

In light of our reflections, it is certainly not possible to interpret Pilate’s notice as a sincere gesture of sorrow, or maybe an awareness, coming too late, of Jesus’ true kingship in a religious sense. None of Pilate’s actions at any point in Jesus’ trial suggest that Pilate ever grasps the true meaning of Jesus’ words and person. Nor does it seem to me to be one last attempt by Pilate to make Jesus’ enemies see the incongruity between their vision of Jesus as a political usurper and the actual appearance of Jesus in all his brokenness on the cross, undergoing a criminal’s death. By now, Pilate is finished with the Jewish chief priests, and is unconcerned about their opinions and support (see Jn 19:21-22).

But I do think that this notice represents a confession of sorts on Pilate’s part. Although I doubt Jesus was ever regarded seriously by Pilate as a threat to his position, he was very much a threat to Pilate as a man and human being. Where Pilate was a shallow human being, Jesus in every word and action was a man of depth. Where Pilate would change his ideological position according to his assessment of its usefulness in gaining the right friends, Jesus was a man whose actions were always consistent with his public teaching and his deepest aspirations, his sense of identity and his mission. Where Pilate was confused, Jesus was clear-headed and calm. Where Pilate tried to win support from the crowd to bolster his position and reinforce his sense of self, Jesus was completely autonomous with reference to public opinion. Jesus was able to express in brilliantly concise terms who he was and why he was now under attack. Pilate had spent his entire life trying to play one side against the other, lying, flattering, bragging, unable to imagine his existence without the trappings of power. And yes, Pilate was power-hungry and highly insecure. He could never get enough power, never enough to feel whole and at peace. Jesus also had a kind of hunger. Pilate sensed it. But Jesus was not hungry for power. He was hungry for souls, he hungered to awaken our hunger for him. Pilate was out for all he could get. Jesus was there to give us everything that was truly important in life and death – in a word, salvation. He longed for us to turn to him, but he never required it.

I believe that some of this dawned on Pilate as Jesus was led away to be crucified. The sniffer-dog in Pilate began to find a kind of power in Jesus that Pilate had not imagined even existed. He realised that Jesus, because of the integrity of his being, did not have power as other men have it – because other men’s power was the kind of power that could be lost. Jesus would never lose his power because he was power. And he was power because he was truth. There was no disorder in Jesus, no ‘parts’ of Jesus that did not spontaneously cleave to and express truth. This was a human power that was much greater than any power Pilate himself had ever encountered in anyone, or would ever be able to possess himself, and he knew it.

In the end, Pilate was thoroughly frightened by this, but he recognized it for what it was, and knew that Jesus’ force in the world would transcend every power structure that had ever existed or ever would exist. Pilate found that this Jesus, the Nazarene, was indeed king of the Jews, and more. He was, in every sense, a threat to Pilate’s human existence. Jesus was king as Pilate would never be. As no man would ever be. Pilate is clear now. This Nazarene, this king of the Jews, must die.